paoloiotti

Teacher Training Resources

Learning Languages: A Natural Talent or Something We Can All Learn?

Learning Languages: A Natural Talent or Something We Can All Learn?

How Listening, Relationships and the Teacher’s Voice Make the Difference

Introduction

How often have we heard people say things like:

“I’m just not good at languages…”

“I understand when I read, but speaking is hard…”

Language teachers hear this all the time. But what does it really mean to “not have a natural gift for languages”? And is it true? Or can everyone improve their ability to learn another language?

In this article, we’ll explore what really affects our language learning: our ability to hear sounds, our desire to communicate, the way we relate to others—and, very importantly, the way teachers use their voice. Drawing on the work of Dr. Alfred Tomatis, we’ll look at how the ear, the body and emotions are all deeply connected when it comes to learning languages.

Can Some People Hear Languages Better Than Others?

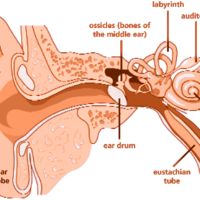

One key factor is our ear’s sensitivity to sound. Different languages use different frequency ranges. For example, British English uses sounds that go up to 6,000 Hz, while Spanish tends to stop around 2,500 Hz. According to Dr. Tomatis, this means that a person who grows up speaking Russian (a language that uses a wide range of frequencies) may find it easier to learn new languages than someone who grows up speaking Spanish.

So yes, part of what we call “talent for languages” may depend on how wide a range of sounds our ear is naturally used to hearing. But even people whose ears aren’t “trained” for those sounds can still learn another language—with help.

More Than Hearing: The Will to Communicate

Being able to hear the sounds of a new language is important—but it’s not everything. Some people hear well but still struggle. Why?

Because learning a language also depends on how comfortable we feel expressing ourselves. Many people—adults and children—have unconscious barriers when it comes to communication. They may be afraid of being judged, of making mistakes, or of not being understood.

This emotional block can be a bigger obstacle than any auditory limitation. The more relaxed and accepted people feel, the more freely they’ll speak and learn.

Singing Helps the Brain (and the Ear)

Dr. Tomatis made a surprising discovery: singing can help people become better language learners.

When we sing, especially using high frequencies, our brain gets more stimulation. Singing activates the inner ear, the memory, and even helps the body take a better listening posture. Singing with good body alignment sends vibrations through the bones—frequencies that help the brain “wake up.”

In the classroom, this has big implications: when students sing before a listening activity, their pronunciation improves significantly. Even just 4 or 5 minutes of singing can make a difference.

Also, songs stay in our memory longer. Why? Because melody and rhythm reach the body first—then the words follow. That’s why songs are easier to remember than plain texts.

Language and Memory Go Hand in Hand

We often think memory is located only in the brain, but that’s not entirely true. Our body remembers too—through movement, rhythm, emotion. That’s why techniques like TPR (Total Physical Response) work so well: when we learn with our whole body, we remember better.

Singing helps connect body and mind. It creates what Tomatis calls an “audio-vocal loop”—a cycle between the ear, the voice, and the body. This loop helps us speak with more confidence and remember what we’ve learned.

So, songs aren’t just fun—they’re essential tools for students who struggle with languages.

The Role of Relationships in Language Learning

But let’s not forget the human side. Language is about connection. If a student doesn’t feel accepted, safe or understood, it will be hard for them to take the risk of speaking a new language.

For real communication to happen, three things are needed:

- Self-acceptance – feeling okay with who we are, including our mistakes.

- Acceptance of others – being open to people different from us.

- The ability to give and receive – real communication means both listening and speaking.

Students—especially young ones—learn how to relate by watching how we teachers relate to them. If we accept them as they are, they’ll be more likely to accept themselves and others.

What the Teacher’s Voice Says

One of the most powerful (but often overlooked) tools in the classroom is the teacher’s voice. It’s not just about what we say, but how we say it.

Our tone of voice communicates more than we think. It can show whether we respect and value our students—or not. And if we speak with tension, sarcasm or disinterest, students can feel it immediately. It affects their motivation and confidence.

Our voice depends on how we breathe. And breathing depends on how we feel inside. A teacher who is calm, centred and self-aware will naturally speak with more warmth and clarity. But if we are under pressure or unsure of ourselves, that comes through in our voice too.

This is why looking after our own emotional balance is not just a personal choice—it’s part of our teaching method. Our students’ success depends, in part, on how at peace we are with ourselves.

Rethinking “Natural Talent”

It’s easy to say “some students just aren’t good at languages.” But that often hides deeper questions: are we reaching them in the right way? Are we offering varied ways of learning? Are we listening to how they learn best?

As educators, we must keep asking ourselves:

- Am I giving time for reflection and creativity?

- Am I valuing all types of intelligence—not just linguistic or logical?

- Am I sending the message: “You can learn this”?

Final Thoughts

Learning a language is more than just memorising grammar and vocabulary. It’s about listening, expressing, connecting, and building confidence. Teachers play a huge role in this—not only through what they teach, but through how they teach it: their voice, their posture, their ability to create a safe space.

Rather than asking “Are my students talented?”, maybe we should ask “What am I doing to make them feel capable?”

After all, as Dr. Tomatis reminds us, listening—true listening—is the beginning of every meaningful change.

Note to readers:

This article offers a practical and accessible overview of ideas I began developing in 1997—ideas that still guide my work with teachers and students today.

If you’re looking for a more structured and theory-rich version, you can download the full academic paper here – [PDF].

Biliography

- Tomatis, A. (1981). La Nuit Utérine. Paris: Éditions Stock.

- Gardner, H. (2011 ed.). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

- Iotti, P. (1996). “How to Choose and Use Songs in Language Teaching.” Resource Practical classroom ideas for teaching languages – ELI (Recanati- AN), No. 2, pp. 11–12.

- Richards, J. C. & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge: CUP.

TEACHER TRAINING COURSES

NEW: USE IT OR LOSE IT! NEW LIFE FOR YOUR ENGLISH. NEW

ENTHUSIASM IN LANGUAGE TEACHING - course map - primary school teachers.

ENTHUSIASM IN LANGUAGE TEACHING - course project - primary school teachers

Collocations - game 1 NEW

Collocations - Conversation - game

Collocations - verbs 1 NEW

Collocations - verbs 2 - go NEW

Conditional - rules NEW

1st Conditional - GAME - NEW (from a great teacher in Romania)

2nd Conditional - GAME - NEW (idem)

3dr conditional - GAME - NEW (idem)

Present Perfect made simple NEW

For - since NEW

Future - Rules & ex. NEW

Future - Game 1st half NEW

Future - Game 2nd half NEW

Sample test NEW

Languages: gift or discipline? Ear Training.The method.

We take a look at the natural ability of the students combined with the teacher’s tone of voice.

Before speaking in a foreing language, we must learn how to listen in a foreing language. NEW

Ear training. La ricerca, il metodo.

Un percorso possibile, anche per gli insegnanti non così esperti in campo musicale (e anche un po' stonati...)

Accedi all'area di apprfondimento del metodo.

Dyslexia & co. - Power point - Download

E chi ha detto che gli studenti dislessici o con disturbi di apprendimento devono per forza avere difficoltà con l'inglese? Quali tecniche? Quali materiali? Ecco alcuni spunti di riflessione in Power Point da scaricare, per cominciare ad approfondire il tema e studiare, senza arrendersi.

Dyslexia - General presentation.

Dyslexia - Extra material.

M.I.T.H.

A practical approach with very young learners: Rods - Numeri in colore.

Teacher Training - Power point - Doc. - Download

ENGLISH - POWER POINT

Before speaking in a foreing language, we must learn how to listen in a foreing language. NEW

Role play .pptx

Writing - introduction. pptx

Writing 2 .pptx

ENGLISH - STUDY PAGES

General principals of motivation.

Learning to breath.

Difficult behaviour in the classroom.

ITALIAN

La predisposizione per le lingue. Che cos'è? Come si alilmenta?

Imparare con il corpo. Fisiologia dell'apprendimento dell'Inglese nella Scuola Primaria.

Extra material - School life

Ecco un po' di materiale da usare in classe, utile per gli studenti della Primaria, e non solo!

Flashcards: classroom language.

Flashcards: feelings.

Flashcards: the weather.

Flashcards: sequence - lesson planning.

Calendar: days, months, numbers.

Perpetual calendar.

Today's visual tasks - gli incarichi di oggi.

Roteglia's group

Stress and intontonation 1

Stress and intonation 2

Classroom language - Gym

Classroom language - Art

Classroom language - Music

Art- conversation

Conditional - game & rules

Geography

Classroom language 1

Classroom Language 2 - Maths